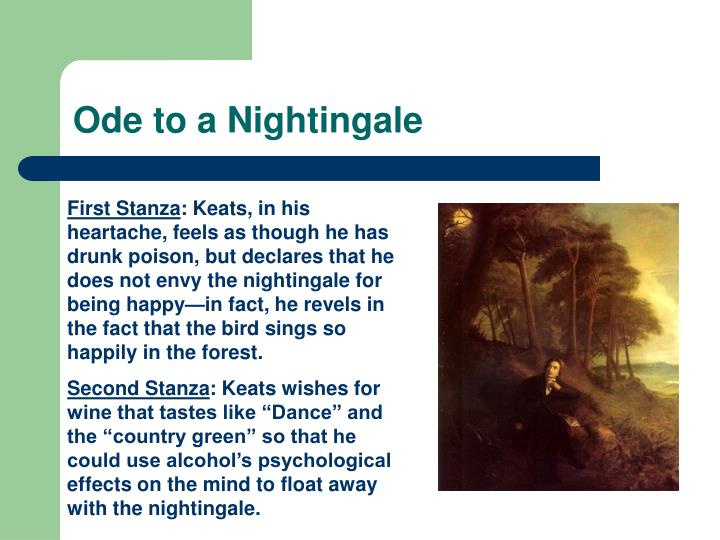

In the final stanza, Keats picks up on the last word of the penultimate stanza – ‘forlorn’ – and so we return to the beginning of ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, with Keats’s ‘heart aches’, just as the word ‘forlorn’ recalls Keats to himself, and to reality. We then leave the world of mythology and religion for the world of full-blown fairyland, as Keats imagines the song of the nightingale accompanying the opening of magic windows that open out onto the sea.

Keats then refers to the Old Testament story of Ruth, who chose to remain with her mother-in-law after she was widowed, rather than returning to her own people (the Moabites): this is why she was ‘amid the alien corn’. However, the ‘immortal bird’ of the nightingale was not made to die, and both high-born and low-born people in ancient times heard the nightingale’s song.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)